The Settled Lands: Back and Around

Credits

Design: Rick Swan

Editing: James Butler

Interior Art: Daniel Frazier

Cartography: Dennis Kauth

Typography: Nancy J. Kerkstra

Production: Paul Hanchette

Don't Call Me A Crank

I'm a farmer first, an elf second. I've also been called an over-the-hill crank who prefers the company of vegetables to people, but that's not fair. True, I live in the outlands of Mistledale, a good 50 miles from the nearest village. True, I'd rather listen to the wind rustle than merchants haggling over the price of cucumbers or would-be warriors jabbering about the dragons they're going to kill someday. I figure when you get to be my age, you deserve a little peace and quiet.

Did I mention I'm an old farmer? I can't say how old - I stopped counting when I bit 300. I'm old enough to remember when the Dalelands were mostly forest, a sea of trees as far as the eye could see; the same for Cormyr and a good chunk of Sembia. Now the Dalelands are mainly roads and villages, cattle pastures and corn fields. Sometimes I think the only reason people haven't ruined the moon and the stars is they haven't figured out how to get there yet.

Of course, if Nature gets the notion, she could shrug off all these villages like a wet hound shakes off water. Maybe one of these days she will.

For now, civilization looks like it's here to stay. It you want to get along, it wouldn't hurt to educate yourself. You don't have to approve of all the changes - I certainly don't - but you can learn why and how they've occurred. Most important, you can learn how to cope with the creatures who call it home. Here's three centuries of observations to get you started.

- Bryn Ohme Thornwood

Part One: Back and Around

Human arrogance never ceases to amaze me. For instance, who decided to call the Dales, Cormyr, and Sembia the "settled lands"? Like they weren't "settled" before people started chopping down trees and ripping up the land with plows? Have we forgotten that the elven woods once stretched from the Storm Horns Mountains to the Sea of Fallen Stars, and were "settled" with deer, rabbits, and wrens? Maybe "unsettled lands" would be a more appropriate name, at least as far as the animals are concerned. Since I was knee-high to an osquip, I've heard people whining about dragon raids and medusae attacks. How can you blame the monsters? After all, it's the humans who are the trespassers.

Humans have built cities and villages since the dawn of time, so I guess the monsters must be getting used to it. Elminster claims he found sealed pots of wheat germ in the Lost Vale, the remnants of a primitive society that existed thousands of years ago. I've heard tales of similar discoveries elsewhere in the world - bone bowls buried in the plains of the Cold Field, records of rice harvests on cave walls beneath the Desertsmouth Mountains.

No one, not even Elminster, knows exactly when it occurred to people to establish villages, but the why is pretty clear. Ancient tribes were faced with two strategies for survival. First, they could live like nomads, stripping an area of all edible plants and animals, then moving on to a fresh site. It was a tough life. Tribes were brutalized by bad weather, hungry predators, and sore feet - annual treks of a thousand miles or more were common.

Alternatively, tribes could settle down and learn to grow their own food and raise their own animals. Much trial and error was necessary to get it right; it's rumored, for example, that a community of stubborn dwarves spent 50 years trying to raise hogs in the Glaun Bog before alligators and giant serpents finally drove them off. In the long run, the advantages outweigh the frustrations. Which would you prefer: trudging across the frozen tundra in hopes of finding a scrawny deer, or butchering a homebred cow in the comfort of your own back yard?

Elminster theorizes that the populations of early villages rarely exceeded a hundred or so residents. They probably would've remained that small forever if not for farming techniques - irrigation and tilling in particular - that allowed them to build up surpluses of food. Easy access to food encouraged families to have more babies; villages soon began to swell like sprained ankles. Some villages merged to form cities so they could minimize military expenses and share religious and commercial facilities.

Cities such as Suzail and Arabel undeniably offer economic opportunities and cultural advantages that small villages can only dream of. Cities have a tendency to get bigger, and the bigger they get, the more headaches they generate. Taxes inevitably go up, not only to finance military and civic projects, but also to fill the coffers of corrupt administrators. Walls and partitions meant to provide security instead contribute to a sense of isolation, even imprisonment. As the population grows, new homes eat up every available space. People suffocate, if not literally, then certainly spiritually.

As for animals, they're faced with four alternatives: They can fight back, adapt, move on, or die off. Many have succumbed to the last. More and more, I predict, will opt for the first.

The Dalelands

Of all the so-called settled lands, the Dales are by far the most hospitable. For the most part, these are places of peace, where farmers are valued more than soldiers, where a man can toil in his rose garden from sunrise to sunset and consider it a day well spent.

The Dale lands comprise a sprawling land mass bordered on the south by Sembia, the west by the Thunder Peaks and the Desertsmouth Mountains, the east by the Dragon Reach, and the north by Moonsea and the Border Forest. Currently, the Dales consist of Archendale, Battledale, Daggerdale, Deepingdale, Featherdale, Harrowdale, High Dale, Mistledale, Scardale, Shadowdale, and Tasseldale. Each community has its own history, government, and outlook; an experienced traveler would no more confuse Battledale for Featherdale than he would an apple for a lemon.

Still, the Dales share as many similarities as differences. They all occupy broad stretches of rolling hills and lush valleys, blanketed with farms, fields, and orchards. All depend on agriculture for economic survival. Each boasts a major town in an accessible location that provides administrative agencies and trade services. Isolated villages, tiny hamlets, and family farms dot the countryside. I've found the people to be self-reliant, independent, and utterly content with their lot in life. It's common for generation after generation to not only live in the same village, but in the same home.

The Lay of the Land

Cormanthor, with its mind-boggling variety of vegetation, probably boasts the world's most fertile soil, but the Dales finish a close second. In the north, Daggerdale and Shadowdale in particular, the topsoil reaches a depth of several feet. The smooth black earth, which gives off an aroma of new grass and spring rain, is so moist that you can pack it into rich clumps. The soil in the south, especially near Tasseldale and Archendale, feels drier, and you'll have to bury your nose in it to enjoy the woody aroma. It's rich enough to grow poppies and pumpkins and everything in between. An acre of Tasseldale farmland can support as many apple trees as two acres anywhere else in the world - the elven forest, perhaps, excepted.

Natural deposits of gems and minerals are as rare in the Dales as friendly feyrs. However, heavy rains in Featherdale recently uncovered what look to be hills of copper ore, and prospectors in Mistledale claimed to have discovered pebble-sized bits of turquoise lining the floor of an Ashaba tributary. Salty minerals in an offshoot of the Deeping Stream have colored the water dull orange and killed nearly all the fish. Featherdale ranchers turned what could've been a calamity into a profitable enterprise. They collect the water in broad, flat tanks, and leave the tanks in the sun. When the water evaporates, the minerals are left behind. The ranchers use the minerals to make salted pork, one of Featherdale's most popular exports.

The Rivers

The Dalelands' rivers - primarily the Ashaba, Tesh, Semberflow, and Deeping - serve as sources of fresh water for drinking, bathing, and recreation. The rivers also supply water for irrigation, a technique pioneered by Shadowdale corn farmers.

A few hundred years ago, a long drought threatened to devastate the corn crops in western Shadowdale. Attempts to dig wells proved futile, as did efforts to haul water from the Ashaba. A young ranger named Lenn Syrrus hooked up a plow to a team of friendly centaurs and dug a ditch from the Ashaba. Syrrus died before completing his work, having suffered a fatal reaction to a wasp sting, but the following spring, Shadowdale farmers pitched in and finished the job. The slope of the land was such that water flowed from the river to fill the ditch. Additional ditches distributed water to the fields. To this day, many still refer to these irrigation ditches as Syrrus canals.

The Haddenbils brothers of Deepingdale were among the first farmers of the settled lands to use dams. The dams, made of granite blocks bound with a waterproof plaster of clay and the webs of giant spiders, retained water in deep pools, dug with the use of a spade of colossal excavation on loan from a gracious warrior. The pools supplied more than enough water for the Haddenbils' thirsty oat fields.

Keltin, a small village of dimwits in northern Featherdale, reportedly built a huge wooden water tower, then commissioned a less than reputable mage to create a spire permanently enchanted with a create water spell. The spire kept the tower filled with water, which farmers could tap as the need arose. It was a good idea, but it came with a high price: The mage demanded half of every year's harvest for rental and maintenance. After they made their payment, the Keltin farmers were left with fewer crops than they'd have had without the water tower. What a deal!

Keltin wasn't the first Dales community to be disappointed by a misconceived water project. Farmers in southern Archendale thought it'd be a good idea to dam up a tributary of the River Arkhen, then divert the water to their apple orchards with a system of small canals. It worked. Then the farmers built bigger dams to create even larger reservoirs, and expanded their orchards until they crowded the river banks. The first big spring storm caused the reservoirs to overflow and flood the orchards. Worse, pressure from the swelling reservoirs eventually caused the dams to collapse. The torrents washed away dozens of farmhouses and drowned nearly a hundred head of cattle before the farmers called it quits and started over again farther south.

Move Over Mold Men

Some people don't have enough sense to stay out of places they don't belong. For example, a century ago, the elders of Lowdner, a tiny but growing community in eastern Battledale, decided to annex a tract of shallow swampland that they planned to lease to young farmers as homestead property. While filling in the swamp with earth, the farmers were confronted by a tribe of mold men. The mold men, who lived in caverns in the adjacent hills, explained that they used the swamp as a burial ground. They pleaded with the farmers to leave it alone, but the farmers had no intention of abandoning their project and told the mold men to get lost. The mold men resisted at first, but were no match for the farmers' weapons and magic. The mold men withdrew from the area and were never seen again.

Within a few months, the farmers finished filling the swamp and began to construct houses. By the end of the year, nearly all the farmers were dead.

The swamp was indeed a burial ground, but not for mold men. The mold men raised thornslingers, deadly carnivorous plants, as companions. The thornslingers routinely produced more seedlings than the mold men could feed. Rather than destroy the excess seedlings, the mold men treated them with special herbs and interred them in the swampy water where they sank to the bottom.

The fresh earth used to fill the swamp activated the dormant seedlings. The thornslingers sprouted in corn fields, in flower gardens, even on the stone walls of farm houses. The thornslingers replaced themselves as fast as the humans could burn, slash, and uproot them. Today, Lowdner exists as a silent garden of pale yellow blossoms. Dusty skeletons entwined with spidery white vines are all that remain of the original occupants.

The villagers of Perekat also sowed the seeds of disaster when they appropriated a pine forest in western Deepingdale. Once the trees were gone, they reasoned, the empty field would make an excellent place to raise pumpkins and watermelons. Within days of felling the first trees, they were approached by a clan of angry korred, The korred used the forest as a site for sacred dances, performed on nights of a half moon. The dances, they claimed, appeased the gods of nature, who in turn supplied them with an ample supply of clear, sunny days for hunting rabbits.

The korred's pleas fell on deaf ears. The Perekat villagers had no intention of sharing the forest and told the korred to stage their dances somewhere else. The korred refused. A week of bloody conflict ensued. The korred attacked with hair snares and stone cudgels fabricated by animate rock spells. Perekat warriors responded with swords, daggers, and spears, augmented by the magic of mercenary wizards from Highmoon. In the end, the korred were no match for fireballs and lightning bolts, and withdrew. As they left, the korred warned the Perekat villagers to expect the wrath of their gods for destroying the dance site. The villagers laughed off the warning; with the korred no longer a nuisance, they resumed clearing the forest.

Today, Perekat is still there, but just barely. Fewer than a hundred die-hards live there now, struggling to eke out a living from their miserable crops. The fields produce dull yellow watermelons the size of sweet potatoes. The pumpkins look like rotten apples, so soft you can push your finger through the skin.

Cormyr

The farmland of Cormyr may be less fertile than that of the Dales, but it'd take an expert to tell the difference. It's a land of rich pastures and lush fields, with corn, oats, and wheat in such abundance that farmers boast that a good autumn harvest could fill the Sea of Fallen Stars with grain. Two mountain ranges serve as borders: the Storm Horns on the west and north, the Thunder Peaks on the east. Not only do the Thunder Peaks inhibit travel, their violent storms ravage the area with lightning powerful enough to incinerate wyverns. Violent weather also plagues the Storm Horns, with pummeling hail that can break bones, and winds strong enough to scatter horses like leaves.

The Lake of Dragons, home to kraken, killer whales, and dragon turtles the size of warships, borders Cormyr to the south. Merchant ships have easy access to Cormyr via the Starwater River, which also supplies fresh water to Waymoot, Eveningstar, and other communities.

Like the Dalelands, Cormyr was originally covered with forest. Decades of clearing trees for farmland has left the King's Forest and the Hullack Forest as the main woodlands. The King's Forest surrounds the cities of Waymoot and Dheolur; Starwater Road, the Way of the Dragon, and Ranger's Way divide it into four neat sections. Most of the dangerous predators have been banished from King's Forest, which now serves as a refuge for deer, wild goats, and similarly docile species. In contrast, green dragons, chimerae, and other monsters stalk the Hullack Forest in frightening numbers, making it Cormyr's most dangerous region. Hullack's rich timber tempts only the courageous and the foolhardy.

The Cormyreans' relationship with the environment has been both exploitive and respectful. Royal decree limits the amount of trees that may be harvested from the two major forests. In Eveningstar and Waymoot, commercial fishermen must obtain permits before casting their nets into the Starwater. The Wyvernwater, centrally located between the King's Forest and the Hullack Forest, remains as clear and blue as the day the gods created it, thanks to restrictions on garbage dumping and magical experiments.

Still, in many places the land bears the scars of human indifference. For centuries, the community of Wheloon used a pond fed by a tributary of the Wyvernflow as a burial ground for war heroes. The bodies decomposed, but not their armor; the rusty water is now unsuitable for fishing or drinking. Priests have blocked efforts to clean it up, fearing retribution from the spirit world.

A few decades ago, rumors of emeralds in the mountains west of Espar generated a mining frenzy. Though no emeralds were found, the prospectors disfigured the mountains with deep trenches and jagged gouges. The rain-filled trenches became rancid pools that contaminated the ground. Today, the area supports scrubweed, a few stubby pines, and little else.

Some of the beautification efforts of Cormyrean aristocrats have also backfired. For the last couple of decades, wealthy landowners in Arabel have sheared away the crabgrass, dandelions, and other natural vegetation on their property, replacing it with gardens of chrysanthemums, geraniums, and roses. The gardens usually require more water than rain alone provides. The landowners make up the difference by arranging to tap hundreds of gallons from the city reservoirs. Farmers without the landowners resources or connections must make do with whatever water remains.

To maximize the number of flowers per square foot, Arabellan aristocrats saturate their gardens with herbs and magical concoctions of dubious value. The soil absorbs only a fraction of these substances. Rain washes the rest away. The patricians shrug off accusations that these practices have adverse consequences, but a stream near Calantar's Way, less than 100 yards away from Arabel's largest private rose garden, contains no aquatic life aside from a few tadpole-sized sunfish. Sludge from a snapdragon field a few miles east of Marsember has run off into an adjacent pond for the better part of a decade. Travelers who camp near the pond often awaken to discover that all of their body hair has fallen out.

Sembia

A few years after I'd established my own farm, I was visited by a smooth-talking stranger dressed in velvet robes and shiny leather boots who professed admiration for my agricultural skills. While jabbering about how opportunity rarely visited a man in my position - a veiled reference, I assumed, to my modest means - he eyed my onion bed, my tomato patch, and the cart from which I sold my wares. Without bothering to ask permission, he uprooted an onion and began counting the roots. I yanked it out of his hand. "The onions are two copper pieces a dozen," I said, resisting the temptation to smack him. "How many do you want?"

"Young man," he said, "I have no interest in your scrawny onions. I wish to buy your farm." He held out a bulging cloth bag. "Seventy-five gold pieces. That will buy a lot of ale."

"'Ware! A dragon!" I yelled, pointing behind him. He turned to look. I booted him in the seat of his fancy britches, sending him sprawling into the onion bed.

I clenched my fists, ready for a fight, but he'd gotten the message. He picked himself up, brushed himself off, and mounted his horse. "The day will come when you'll beg to be a field hand in Daerlun," he hissed, then rode away.

That was my first contact with a resident of Sembia. Any desire I had to visit Sembia vanished that day.

The little I know of Sembia comes front traveling merchants and chatty rangers. The land itself resembles that of the Dales and Cormyr, a verdant quilt of broad plains and rolling hills. The forests that once stretched from the Cold Field to the Neck of the Sea of Fallen Stars have given way to endless acres of farms. Busy seaports dot the coast. A handful of crowded cities, chief among them Daerlun and Ordulin, are home to wealthy traders, ambitious politicians, and struggling commoners. Because of their tradition of detachment, nurtured by the arrogance of the leaders, Sembians view outsiders like mice view cats - or perhaps, more appropriately, like cats view mice.

Despite their arrogance, Sembians have proven to be reasonably attentive caretakers of the land. Most farmers rotate their crops so as not to exhaust the soil, and many allow elk and deer to share their fields, resisting the temptation to reach for their bows. Some villages establish hunting seasons with rigid limits so animal populations can recover. I've heard of game reserves spanning dozens of square miles, including one west of Umrlaspyr reputed to be the world's largest refuge for giant opossums.

Farms

It seems like you can't walk ten yards in the settled lands without stepping in a wheat field or pumpkin patch. I'd guess that 70 percent of Cormyreans make their living from farming. In parts of the Dalelands, it may be closer to 90 percent.

Farm sizes vary according to the quality of the land and their proximity to villages. In the isolated regions of northeastern Sembia, where the sandy soil supports only the hardiest grains, farms rarely exceed a few acres, producing enough food for a small family and a couple of horses. In Cormyr, where the soil is more fertile, farms may comprise 20-80 acres. In some instances, a village may claim ownership of all farmable land within a mile circumference; village elders assign plots of 2-10 acres to selected families. The families keep a percentage of the crops, usually about half, and turn over the rest to the elders, who trade it with neighboring villages for tools, weapons, and other goods. Some of the communal farms in Featherdale cover 100 acres, while the government-supported estates of Suzail average two or three times that size.

Farms near cities usually fare the best. Cities can muster the economic resources to build dams and finance irrigation projects. It's easier to sell crops and livestock in a city, and easier to buy equipment and supplies. Progressive communities, including Suzail and Arabel, will loan farmers money to buy land or see them through lean years. The inns, taverns, and shops provide outlets for information; you're more likely to hear about innovative irrigation techniques and new markets for cattle while making business contacts than by enjoying the solitude of your fields. If a farmer without access to a city wants to get rich, he'd better find a diamond mine in his corn field.

Just as settled lands' farms come in all sizes, they also come in all types. Fruit and vegetable farms proliferate in the Dalelands. Mistledale and Battledale farmers raise celery, tomatoes, onions, potatoes, carrots, and watermelons, while Cormyr produces hundreds of acres of apples, peaches, grapes, raspberries, and blueberries.

Fruit and vegetable farms usually require smaller amounts of land to generate acceptable profits - in Cormyr, an acre of raspberries earns as much as twenty acres of wheat - but they also require a lot of labor. While a corn farmer relaxes in the winter, an apple grower is busy pruning dead branches. A wheat farmer uses scythes and other tools to help harvest his crops; a blueberry farmer picks his fruit by hand.

Wherever there's a meadow for grazing, there's bound to be a dairy farmer. Most raise cattle and goats, though farmers in Deepingdale have prospered from selling deer milk. Tulbegh farmers are renowned for their osquip milk, which is mixed with seaweed mulch to make baby food. A dairy farm operated by a single family usually maintains 4-15 head of cattle, or about twice as many goats. Cattle and goats are milked twice a day, deer once a week, and osquip about once a month.

Farmers milk livestock by hand, though goat herders in Harrowdale have experimented with trained banderlogs. The banderlogs compete with each other to see who can milk the most goats in the shortest amount of time, which frees the farmer to pursue other chores. Goats seem to prefer a banderlog's touch to that of a human, and often fall asleep on their feet while the banderlogs merrily milk away.

Poultry farmers, common throughout Cormyr and parts of Sembia, not only raise chickens, but quail, ducks, and turkeys. A typical poultry ranch handles anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred birds, though Colton Bachman, who operates a ranch east of Waymoot, raises 3,000 chickens every year. Bachman makes his money from eggs and meat, as well as the chicken manure he sells by the wagonload to affluent Cormyreans for garden fertilizer. Bachman's cousin, Geremi Bergo, claims to have the world's largest boobrie ranch, located south of Dheolur. When Bergo's plans to market roast boobrie fell through - boobrie meat is as tough as leather and tastes like old parchment - he rented them out as exterminators. Snakes, lizards, and other vermin have been virtually eliminated from Dheolur homes, thanks to the voracious appetites of Bergo boobries.

Grain, however, remains the principal money crop for farmers across the settled lands. Oat, alfalfa, and wheat fields fill hundreds of acres around Cormyr, while corn, barley, and rye feed families throughout the Dales. Farmers from Shadowdale to Selgaunt employ the same agricultural techniques, which haven't changed much in the last hundred years. They begin the new season by plowing the ground to stir up the soil, then space the seed grain far enough apart so new plants won't have to compete with each other for nutrients. Fields are regularly watered and weeded. Farmers preserve the soil by alternating the type of crop grown in a particular field every year or so.

Farmers have not always been this conscientious. In the early days, primitive farmers would locate a promising field or forest, clear out all the vegetation and trees, then plant whatever they felt like. Sometimes the crops grew, sometimes they didn't. The next year, they'd try again in the same place, moving on when crops refused to grow. This crude technique literally sucked the life from the ground. Flourishing sunflower fields and hickory forests became bleak plains of dust, suitable for dung beetles and ragweed, and not much else.

If left alone, depleted fields eventually recover. Consider the stretch of land informally known as Black Plain, located midway between the East Way and the Immer Trail, 40 miles east of the Hullack Forest. As old-timers may recall, Black Plain once was the site of a towering oak forest. About 50 years ago, homesteaders from Cormyr burned and chopped down the oaks, hoping to turn the area into farmland. When digging irrigation ditches from the Wyvernwater proved too difficult, they abandoned the project.

Today, Black Plain consists of three distinct sections. The northern section was deforested last, and will therefore be the last to revive. Currently, the land is barren, except for some ant hills and scattered burdock. The middle section, however, shows more signs of life; milkweed and thistle have replaced the burdock, attracting butterflies, goldfinches, and wild rabbits. Chokeberry shrubs and tangled honeysuckles have spread over the hills and valleys, providing cover for wild chickens and deer. Badgers and wolves, lured by the smell of prey, are moving in and raising families.

Since the southern section was the first to be cleared, it will be the first to renew. New oaks are peeking through the soil, the seeds carried by the wind and dropped by squirrels and birds. Recovery, however, proceeds at a snail's pace. Few of these oaks have grown more than a foot or two, and the animal population remains low. It may be centuries before the forest returns to anything resembling its original glory, but it will return eventually, providing, of course, farmers keep their distance.

Weather

Except for clouds that bark like dogs and lightning bolts that can be picked up and carried, the weather in the settled lands is pretty much like that in other temperate areas of the world. Summers are hot and winters are cold, but not intolerably so. Most spring days are as soothing as a warm bath. Rain falls steadily throughout the growing season. Compared to undeveloped regions like the elven forest, the settled lands are less humid and a bit drier. Since we have a shortage of dense forests to act as wind breaks, we're also subjected to stronger winds.

Travelers may be shocked to discover the weather disparities between the cities and the surrounding countryside. Hardwood buildings and stone walls retain heat, so cities tend to be warmer than open fields. Because buildings block and redirect air currents, cities experience fewer strong winds.

Elminster has compiled climatic averages for the region where I live. Though Cormyr is a little colder in the winter and parts of Sembia receive more rain, these figures should give you an idea of the temperate conditions prevailing in the settled lands.

Climatic Averages For Mistledale

| Temperature (Spring) | 69 degrees F |

| Temperature (Summer) | 80 degrees F |

| Temperature (Autumn) | 62 degrees F |

| Temperature (Winter) | 38 degrees F. |

| Low Temp. (Year) | -20 degrees F |

| High Temp. (Year) | 98 degrees F. |

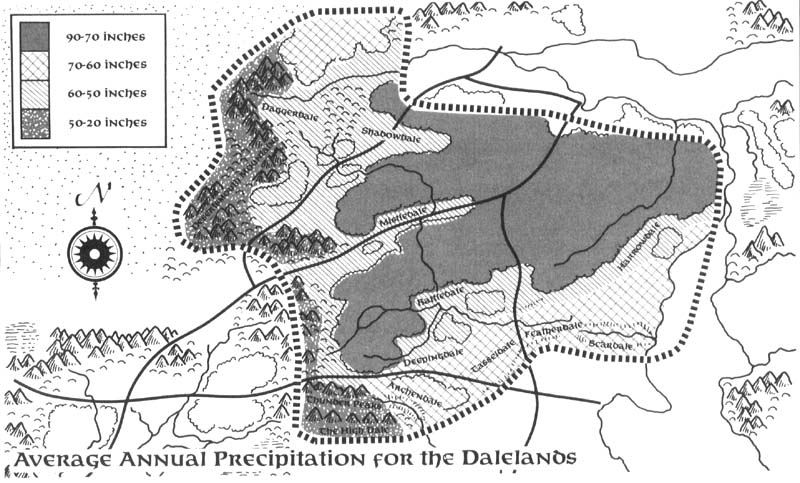

| Annual Precipitation | 50 inches |

| Days With Snow on Ground | 40 days |

Daily Weather

To determine the temperature on a particular day, find the average temperature of the current season listed in the Climatic Averages section above. Roll 1d10. If the result is odd, subtract it from the average. If the result is even, add it to the average. For example, if the season is autumn and the roll is 7, the temperature is 58° (65 - 7).

To determine the prevailing weather, roll 1d20 and consult the following table.

Prevailing Weather in Mistledale

| d20 Roll | Weather* |

| 1-7 | Clear |

| 8-11 | Partly Cloudy |

| 12-15 | Overcast |

| 16-19 | Precipitation1 |

| 20 | Extreme weather2 |

| *For random determination of wind velocity, roll 1d6; 1-3 = less than 10 mph, 4-5 = 10-20 mph, 6 = more than 20 mph. To determine the direction of the wind, roll 1d4; 1 = north, 2 = east, 3 = south, 4 = west. 1 Roll 1d6; 1-2 = up to 1/2 inch; 3-4 = 1/2 to 1 inch, 5 = 1-2 inches, 6 = more than 2 inches. 2 Hailstorm, blizzard, heavy fog, tornado, etc., as decided by the DM. | |

The DM may make adjustments to this list when special events exist (such as magical manipulation of the weather), when unusual conditions prevail (such as long droughts), or in exotic terrain (such as mountain peaks).

"Temperate," however, is somewhat of a misnomer. A typical year can bring dizzying temperature swings. A summer day can get hot enough to cook an egg in its shell. Winter can get cold enough to make a white dragon wear mittens.

Storms are likewise unpredictable; a soft breeze in the morning can precede a gale-force wind at night. Autumn can bring hail the size of apples. A spring tornado can siphon up a farmhouse in Daggerdale and dump it into Lake Sember.

Attempts to control the weather have met with mixed success. To ensure sufficient rain, elven farmers south of Spiderhaunt Woods offer pots of honey to their gods before spring planting. Sometimes the rain comes, sometimes it doesn't, but the honey almost always attracts bears and badgers. In Blustich, a small community east of Hermit's Wood, the villagers stage elaborate dances with gourd rattles and log drums to conjure up winds strong enough to blow nuts off the hickory trees. The villagers usually end up with enough nuts to feed an army of squirrels, but I suspect their good fortune has more to do with Blustich's proximity to the winds blowing off the Lake of Dragons than a divine response to bad music.

Many farmers fear heavy rains as much as droughts, as excessive precipitation can wash out crops and cause floods. Farmers in southern Harrowdale once addressed the problem by hiring Kaymendle Skrip, a well-meaning but inept Sembian wizard who claimed he could conjure an apparition that would frighten away storm clouds. The apparition, resembling a cloud bank shaped like an overweight war dog, howled and snarled whenever a dark sky threatened heavy rain. The storm clouds ignored the howling apparition and dumped rain as fiercely as ever. Kaymendle skulked out of town, leaving the apparition behind. To this day, the dog cloud continues to float over the fields of southern Harrowdale. It whimpers like a puppy a few hours before light sprinkles fall, barks like a hound prior to a typical summer rain, and howls like a wolf to herald a major thunderstorm. Area farmers are still at the mercy of heavy rains, but at least now they know they're coming.

Kaymendle had better luck in the Thunder Peaks. Ranchers north of the Hullack Forest were fed up with the lightning storms that rolled off the mountains; it was not unusual to lose dozens of cattle in a single storm. Kaymendle convinced the ranchers he could permanently enchant the atmosphere to generate lightning bolts so heavy they'd fall out of the sky before they could do any damage.

The enchantment succeeded - to a point. A few lightning bolts did indeed solidify and drop like rocks, but anyone who touched a fallen bolt risked a fatal shock. Some of the fallen bolts could be handled without fear of injury, and could even be thrown like spears, but most of the lightning was unaffected and remained in the sky. The storms continued to lay waste to the ranches. Kaymendle had again failed to deliver, and was forced to flee the area before the angry ranchers impaled him on one of his own bolts.

Undeterred, Kaymendle retreated to a secluded laboratory in the wilds of Arch Wood. He is rumored to be working on a spell for elastic snow, which bounces back to the sky as soon as it strikes the ground.

Kaymendle Effects

| d6 | Effect |

| 1-3 | If the bolt is touched or otherwise physically disturbed, it vibrates and emits a shower of soft sparks for 2-5 (1d4 + 1) rounds. The sparks are harmless. At the end of this period, the bolt disappears in a flash of light. If left alone, the bolt vanishes in 1 - 2 days. |

| 4 | As above, except at the end of 2 - 5 rounds the bolt explodes. All characters within 10 feet of the bolt must save vs. spell. Those failing the roll suffer 6d6 points of damage; those succeeding suffer half damage. If left alone, the bolt vanishes in 1 - 2 days. |

| 5-6 | The bolt may be handled and carried. It may also be thrown like a spear and used as a weapon. The target must be at least 10 feet away; if closer, the hurled bolt does no damage and disappears in a harmless flash of light on impact. If not using the weapon proficiency rules, make a normal attack roll with a -3 penalty. If using the weapon proficiency rules, characters with the spear proficiency have their normal chance to hit; others suffer the penalties shown on the Proficiency Slots Table in Chapter 5 of the Player's Handbook. If the bolt hits, the target suffers 6d6 points of damage; half damage if he makes a successful save vs. spell. The bolt may also be thrown against any solid object, such as a stone wall; an object suffers half damage if it successfully saves against electricity (use the Item Saving Throws). |

A Kaymendle bolt can be thrown only once; it disappears on contact, regardless of what it hits. A bolt will not ignite combustibles, nor will it reflect from a solid surface (like some versions of the lightning bolt spell).

If not used as a weapon, a Kaymendle bolt disappears in a flash of light within 1-2 days after its discovery (or as determined by the DM)

Kaymendle Lightning Bolts

The atmosphere in and around the Thunder Peaks still produces an occasional Kaymendle lightning bolt. A Kaymendle bolt may be lying on the ground, lodged in a tree, or even floating on the surface of a pond. In most cases, Kaymendle bolts will only be found within 50 miles of the Thunder Peaks.

Typical bolts are 5-10 feet long and resemble jagged spears of smoky glass that radiate a soft golden light. Bolts that can be handled (see below) weigh only a few ounces and feel like sticky cotton. These bolts are as flexible as bamboo; if broken, they dissipate in a flash of light.

When a character encounters a Kaymendle bolt, the DM should secretly roll on the following table to determine its effect. A character can't tell a bolt's effect merely by looking at it; he'll have to discover it by magic (a true seeing spell would work) or by trial and error.

Seasons

The Dales experience distinct seasons, each lasting about three months. Though Cormyr has longer winters and shorter summers, and more rain falls in Sembia during the spring, seasons are pretty much the same throughout the settled lands.

Spring lasts from Ches through Mirtul, with temperatures settling in the 70s by the end of Tarsakh. Most days feature blue skies and gentle breezes, though thunderstorms become more frequent in the season's waning weeks. Mirtul brings an occasional tornado, most often in southern Harrowdale and the plains north of Cormyr. On clear days, farmers keep busy with planting, which must be completed by the end of spring to maximize the chances of a good harvest.

Summer lasts from Kythorn until Eleasias. Rain drenches the plains throughout Kythorn, sometimes as often as every other day. Temperatures peak in late Flamerule, hovering in the high 80s for the rest of the season. Most crops mature in the summer, and to ensure their survival, farmers must remain vigilant for weeds, insects, and diseases. Carrots, lettuce, and other vegetables are harvested; what the farmer doesn't set aside for personal use, he markets at the nearest village.

In autumn, lasting from Eleint through Uktar, farmers race to bring in their grain before the first frost. The chance of severe weather increases as autumn draws to a close, particularly in the areas adjacent to the Thunder Peaks and Storm Horns. Hailstorms can shred corn stalks, and torrential rains can turn wheat fields to pools of muddy water. As Marpenoth approaches, temperatures drop steadily and skies become bleak and gray.

Winter hits in mid-Nightal. By the end of Hammer, light snow dusts most of the settled lands. Temperatures hover around freezing and snow rarely exceeds a few inches until early Alturiak, which brings long stretches of sub-zero weather and blizzards that can dump mountains of snow overnight. Since few crops can grow in snow-covered fields, farmers pass the winter by tending to ailing livestock, hobnobbing with neighbors, and planning next year's harvest.

Plants

Norl Maywren, a retired elven carpenter living in all cottage north of the Hullack Forest, has spent the last decade carving life-size busts of his great-grandchildren. He carves each bust from a different type of wood. So far, he has 43 busts, and is still working on the boys. Considering the variety of trees in the area, he expects to run out of kids before he runs out of wood.

The number of tree species in the settled lands may not match that in Cormanthor, but I bet it's close. The Dalelands are lush with birch, ash, poplar, and walnut. Cedar, hickory, hawthorn, crabapple, peach, and pear trees flourish in and around Cormyr. Sablewood and chestnut groves dot the plains of Sembia. Oaks, pines, maple, beech, and fir are everywhere. The variety of shrubs, herbs, and flowers is similarly staggering; if it blossoms, bears fruit, spouts leaves, or makes you sneeze, it probably grows somewhere in the settled lands.

The settled lands also have their share of unusual plants. A few examples:

Chuichu trees resemble miniature hickories, about three feet tall. Found mainly in the forests near Battledale, chuichu trees produce cone-shaped yellow berries that dissolve in water to make a delicious, cinnamon-flavored beverage.

Blueleaf trees, which can be found in large groves in the northern edge of Hermit's Wood, look like large maples. Their leaves radiate a faint blue light. The processed leaves produce a rich blue dye; when burned, the wood generates immense blue flames.

Eldella ferns sprout near the bases of giant mushrooms growing near the perimeter of the Hullack Forest. If lightly toasted, the ferns may be fed to catoblepas, who find them quite tasty. A meal of eldella neutralizes a catoblepas's deathray for 24 hours.

Barausk trees, located in Harrowdale and Deepingdale, resemble beeches, their black branches and white trunks covered with three-inch thorns. When cut from the trunk, the branches turn as hard as iron in 24 hours. Soldiers and hunters find that barausk branches make excellent - and deadly - spears, arrows, and staffs.

Not all of the Settled Land vegetation is native to the region. Humans have intentionally introduced some plants, others have been introduced by accident. In most cases, non-native vegetation has had no significant effect on the environment. Moon corn, a strain with crescent-shaped kernels imported from Vaasa, grows side by side in Sembian fields with regular corn. Giant sunflowers, reaching heights of 20 feet or more, were brought in from Spiderhaunt Wood to beautify the estates of Cormyrean aristocrats. Despite warnings that the immense plants would require inordinate amounts of moisture, it turned out that the giant sunflowers required no more water than daisies. Rosecork trees, native to the Isle of Prespur, now flourish in the southern tributaries of the Wyvernwater, thanks to the efforts of a Wheloon importer. Rosecork wood is virtually fireproof and is becoming increasingly popular with builders.

In other instances, however, the introduction of non-native vegetation has had unexpected - even tragic - consequences.

A swarm of bees contaminated a Daggerdale clover field with the pollen from jade cocoa, a rare plant from the Border Forest. The pollen created a new species of clover with triangular brown leaves and the scent of mint. Cattle found the brown clover irresistible; unfortunately, it was also poisonous.

The skypine, a slender conifer with bright blue needles, was introduced to Cormyr from the Borock Forest. The deep-rooted skypines were planted along the banks of irrigation ditches to prevent soil erosion. Unknown to the importers, the skypines are also a favorite roost of stirges, which arrived by the hundreds when the skypines matured.

Animals

Why do some animals get along with people, while others remain hostile and wild despite all efforts to domesticate them? Why does a dog lick your fingers, a wolf nip them off? Why will a horse agree to pull a plow, while a zebra would rather be whipped than harnessed?

Animal dispositions seem to be as innate as fur color and food preference. A dog comes when called, a cat sits and stares. A monkey can learn to open locks with a key, but a minotaur lizard can't figure out how to push open a door. Animals with a natural distrust of humanoids will usually resist all efforts to be tamed. You can cage a giant weasel in your backyard as long as you like, but he'll probably run for the woods - or lunge for your throat - at the earliest opportunity.

Domesticated Animals

Of all the animals that live and work with people, none has proven more useful than the horse. Originally, the horse was considered to be little more than a tall cow, its flesh used for meat, its hide for leather. A few small villages along the Deeping Stream still raise horses for meat, but elsewhere people have learned to prize horses for their speed, intelligence, and strength. A good horse can plow a small corn field in a day's time or drag a sleigh through 40 miles of snow without a rest. It can find its way home on the darkest of nights, alert its owner to a fire in the barn, and defend a fallen rider from a pack of hungry wolves.

Even in the largest cities, horses remain valuable commodities. They provide transport for soldiers, companionship for peasants, and recreation for aristocrats. Affluent citizens often build elaborate stables for their steeds, with separate rooms for water troughs and hay stacks. Following a fever epidemic in Eveningstar that killed off most of the horses, many of these stables were sold to enterprising businessmen who converted them into luxury apartments.

If horses are the most useful domesticated animals, cattle must be the most popular. Any farmer with a pasture raises at least a few head of cattle, because they're virtually maintenance-free. Leave them alone, and cattle will spend their days turning grass into milk and beef; add a fruit tree and a vegetable garden, and a farmer has all the food his family will ever need. Large cattle can be taught to pull wagons and plows. While they lack the strength and stamina of horses, they're also less temperamental; point a cow in the right direction, poke her with a stick, and off she goes.

Pigs won't do any work - they're too stubborn and probably too smart - but their meat is delicious. They can be raised just about anywhere, because they'll eat just about anything. Pigs thrive on corn, fish, snakes, insect larvae, worms, eggs, fungi, seedlings, or garbage. Many claim that foraging pigs taste better than those raised on grain. Some Scardale farmers let their pigs run wild in the woods, eating whatever they can find. When butchering time arrives, they lure the pigs back to the farm with the smell of roasting corn.

Many other domesticated species can be found throughout the settled lands. Chickens are raised for meat, eggs, and protection; the fierce fighting hens of Arabel, with claws as sharp as razors and beaks like tiny spears, can chase away small wolves. Farmers keep cats in their barns to hold down the mouse population. Sheep provide mutton and wool. Beekeepers in Eveningstar sell honey to bakers for pastry, the wax to healers for medicines, and the stingers to wizards for magical research. Cormyreans raise ferrets and bluebirds as pets. Sembian sailors keep roosters on board ships for good luck.

Dangerous Animals

If any so-called "normal" animals seem bent on making life for humanoids as miserable as possible. Some are merely annoying, such as the raccoon who slips through your kitchen door in the middle of the night to rummage through the cupboards, or the squirrel who chews the shingles off your roof to make a nest in the attic. Others, however, can be as mean as a troll with a toothache, like the wolverine who'll chew off your foot if you step in its lair, or the covetous raven who may mistake your eyeballs for gems.

Of all the animals that plague the settled lands, none causes as much trouble as the common rat. Apparently, rats believe farms exist for their benefit. They infest barns, storehouses, even pigsties in staggeringly high numbers. Their appetite knows no limits; they'll eat grains, fruits, vegetables, chickens, kittens, and each other.

Sinda Kayhill, a friend of mine who farms in Shadowdale, opened the door to her stable one morning and was greeted by a tidal wave of rats. The rats knocked her down and stampeded across her back. Sinda hugged the ground and said her prayers, expecting the rats to eat her alive. Instead, the rats thundered toward the woods and disappeared. Still trembling, Sinda rose and stumbled into the barn. No wonder the rats had left her alone - their stomachs were full. They'd stripped the flesh from a dozen cattle.

In addition to damaging property, rats carry diseases that can wipe out humanoid communities. Five years ago, the chicken farms of Beaverwood, a small village on the western shore of the Wyvernwater, attracted hungry rats by the thousands. The rats brought a contagious lung disease that infected the entire population. By summer's end, all of the villagers were dead. Cormyrean administrators wouldn't let anyone enter the infected village, including relatives of the deceased. After consulting with religious leaders, who conducted funeral rites from platforms overlooking the village, the administrators ordered Beaverwood burned to the ground. About half the rats were incinerated. The rest escaped.

Livestock farms, particularly those near forests, are as likely to be victimized by wolves as rats. Wolves have a voracious appetite for sheep, pigs, and calves, and won't let a couple of farmers stand in their way of a meal, even if the farmers carry battle axes and long swords. Wolves pose a particular threat in winter when wild game becomes scarce.

Though rare in most of the settled lands, baboons thrive in the Hullack Forest and in parts of the Arch Wood. They've learned to count on humanoid communities as sources of food the year round. Baboons strip fruit orchards in the spring, raid corn fields in the summer, and break into homes in the winter, smashing windows or gnawing down doors if necessary. Generally, baboons remain oblivious to humanoids. If left alone, a baboon will pick apples alongside a farmer, or nibble an ear of corn while hitching a ride in a farmer's wagon. If harassed, a docile baboon becomes a vicious aggressor, leaping on its tormentor in a rage of screeches and slashing teeth. If you encounter a female baboon, leave her children alone. Should an infant baboon die at the hands of a humanoid, the mother will replace it with a humanoid baby, preferably one of the perpetrator's offspring. If necessary, the mother baboon will enter the perpetrator's home at night and snatch an infant from its cradle.

While most experienced travelers are familiar with poisonous serpents and insects, I'd be remiss if I didn't warn you of some of the unusual venomous creatures in settled lands. For instance, a field mouse that dwells in the forests of Farrowdale sports a pair of curved incisors that continually drip a milky fluid deadly enough to fell a war horse. The mice lair in rotten logs and abandoned gopher holes, eating insects and grubs. Farrowdale mice are whirlwinds of frenzied activity. They dart after blowing leaves, pounce on blades of grass, and snap at any creature who wanders by, regardless of its size.

The copper opossum, a native of the Cormyr foothills, is as shy as the Farrowdale mouse is aggressive. It spends most of the day eating weeds and seedlings, rolling itself into a tight ball whenever it feels threatened. If handled, the opossum kicks with its hind legs, piercing its oppressor with tiny spikes located just above its feet. The spikes secrete poison that causes paralysis. Incidentally, the opossum's fur contains actual copper; if processed by a knowledgeable craftsman, the fur of a mature copper opossum yields 2-5 pounds of metal.

The gray flatfish of the River Arkhen resemble granite stones about a half-inch thick and a foot in diameter. They lie perfectly still on the bottoms of shallow streams, eating any algae or refuse that happens to drift by. Travelers wading across streams may step on these fish by accident, as they're virtually indistinguishable from stones. Pressure on the flatfish's back causes dozens of inch-long spines to become erect; the rough spines can easily penetrate shoe leather. The spines inject poison that inflicts extreme, debilitating pain lasting as long as a week.

The cobra trout, which lives in the Deeping Stream, is one of the few fresh water fish with a poisonous bite. Extremely territorial, the cobra trout lunges at any creature that comes within a few feet. This fish can exist on dry land for as long as an hour, using tiny fins to haul itself along the ground. Fortunately, its bright silver scales make it easy to recognize and avoid.

Poisonous Creatures of the Settled Lands

For the Farrowdale mouse and the copper opossum, use the normal mouse and opossum statistics. If either creature makes a successful attack, the victim is poisoned.

Poison Effects Table

| Creature | Onset Time | Result of Failed Saving Throw * |

| Farrowdale mouse | 1-4 rounds | Victim doubled over in pain for the next 2-5 (1d4) hours; can take no actions during that time. |

| Copper opossum | 1 round | Victim suffers effects similar to those of a temporal stasis spell. Effects persist until victim benefits from dispel magic, neutralize poison, temporal reinstatement, or a comparable spell. |

| Gray flatfish | 2-8 rounds | Victim experiences intense pain throughout his body for next 2d4 days. During that time, he makes all attack rolls and ability checks at a -2 penalty. |

| Cobra trout | 1-4 turns | 1d6 Con initial, 2d6 Con secondary damage |

| *A successful saving throw means no damage. Victims of the Farrowdale mouse, copper opossum, and gray flatfish receive no modifiers to their saving throws. Cobra trout victims receive a -4 modifier. | ||