The Great Gray Land of Thar

Credits

Design: Anthony Pryor

Editing: Elizabeth T. Danforth

Interior Art: Daniel Frazier

Cartography: Dennis Kauth

Typography: Nancy J. Kerkstra

Production: Paul Hanchette

A-Ranging I Will Go

Talyssa Strongbow is a ranger who has traveled extensively throughout the Forgotten Realms. A sailor on the Moonsea, an adventurer in the Reaching Woods and the Forest of Wyrms, and a mercenary scout who fought against the hordes of Dragonspear, she has most recently made her living as a guide in the Great Gray Land of Thar. Talyssa is a flinty, somewhat grim woman who nonetheless shows deep human feelings when she is of a mind. The Land of Thar is widely reputed to be a barren wasteland with little to recommend it to adventurers, explorers, or merchants, but her account, given in her typically cynical and world-weary style, may go far in changing the region's reputation. I present her account in its entirety, with a few of her choicest expletives removed and replaced with less offensive language.

The Great Gray Land of Thar is a region most sensible individuals will tell you to steer clear of. Mind you, the average "sensible" inhabitant of Faerûn is probably a seedy country bumpkin fresh off a turnip cart, chewing thoughtfully on a week-old stalk of grass as he scratches his filthy, vermin-infested head and ruminates on how much he can sell his prize possum-hound for.

I've never put much stock in the pronouncements of such people, and when I discovered the consensus among the hayseed-and-huckleberry crowd was to avoid Thar, I immediately made plans to go there. You see, after what I had foolishly considered a "life of adventure," I had decided to settle down and live the gracious country life. Unfortunately for me, I found myself in a tiny Cormyrean community where the farmers lavished more adoration on their dogs than on their wives, no one had ever even seen a book let alone bothered to learn how to read, and the most exciting event was getting together and watching old Uncle Melf's barn burn down.

After about six months of sampling the questionable luxuries of the back country, I had to face the fact that I was intensely unhappy. Accordingly, I dismissed my servants (who seemed inordinately delighted at the chance to get back to wallowing with their pigs on the family farm) and sold my villa to the local robber baron, who had been drooling over the place for months.

My travels took me northeast to Hillsfar. (I avoided Zhentil Keep as its rulers seem to have placed a price on my head for some unfathomable reason.) By carrack I traveled across the Moonsea to Melvaunt.

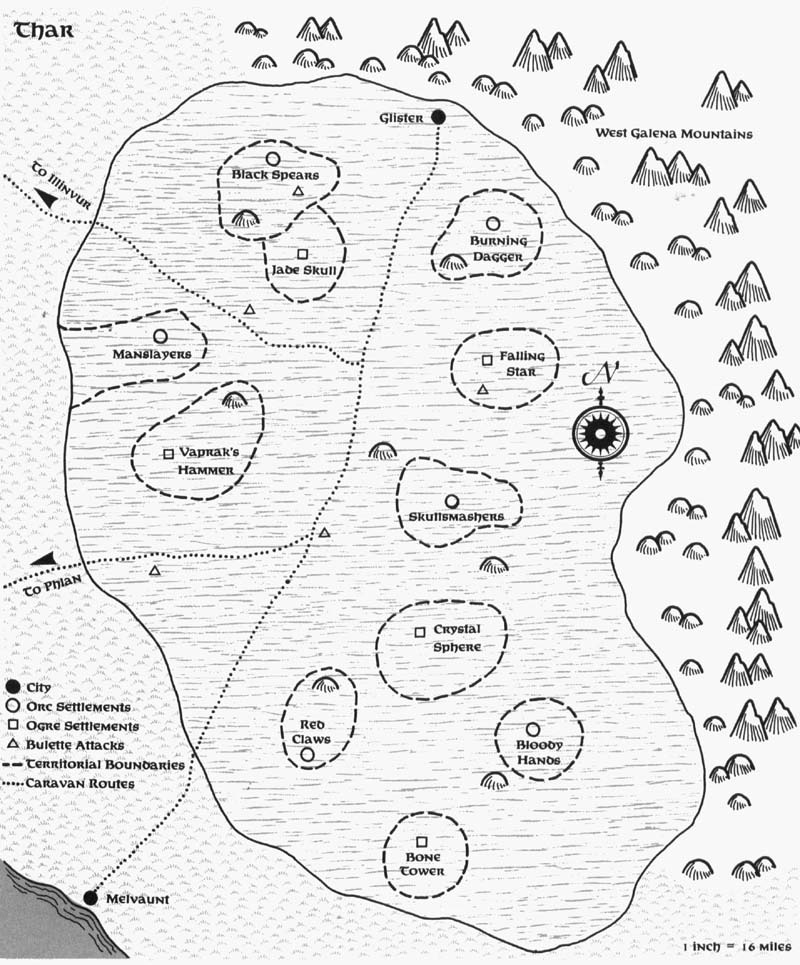

Once in Melvaunt, I discovered that the bumpkins' view of Thar was somewhat flawed, as the views of bumpkins often are. Activity in the Gray Land has increased enormously in recent years, with the discovery of rich mineral deposits in the West Galena Mountains. Caravans across the treacherous terrain to the frontier settlement of Glister were regular, if not exactly common, and there was much work for experienced wilderness scouts like me. The Thay Rangers - an informal organization of scouts, guides, rangers, and hunters.protect and look after the interests of freelancers in the region, and its leader, an aged mercenary named Khalvo, seemed delighted to accept me as a member.

With this in mind, I joined a large northbound caravan and, after forcibly convincing the caravan master that my services as a scout did not include services as his "special friend," began a lucrative career as a Thay Ranger.

Part One: The Land of Thar

At first glance, the Great Gray Land seems about as welcoming and fertile as an orc's armpit. Vast, seemingly endless steppelands covered in gray-brown grasses, with occasional stands of shaggy pines, rocky outcroppings, and marshy wetlands, Thar has the added onus of a reputation as home to vast bands of orcs and ogres.

While the region is inhospitable, to say the least, I found it a place of great fascination and adventure, especially for a bored ranger grown tired of village life. The steadily-increasing human activity in the region has led to a steadily-increasing interest in Thar, especially by merchants and those looking to exploit the mineral wealth of the West Galenas.

The Seasons

Thar's climate is best described as typical of a high steppe region, with its altitude contributing to its relatively harsh climate.

Spring brings heavy rains and a profuse bloom of wildflowers and grasses. This period, which often lasts less than a month, comes late, even as the rest of Faerûn is sweltering in summer's heat. At this time, the Great Gray Land is actually sprinkled with patches of bright green.

Summer comes quickly, ravaging the steppes with heat and humidity. Grasses wilt and flowers die. A few weeks after the advent of spring, Thar is back to being the Great Gray Land.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when summer ends in Thar, or when fall finally turns to winter. Gradual cooling grips the plains, further stressing the surviving plants, and sending animals into a frenzy of feeding or food-storing. Among the caravans, winter officially begins with the first frost.

Once temperatures reach the point that the ponds and streams actually freeze, winter descends quickly, blanketing the land with snow. Caravan traffic ceases, and the region's intelligent residents hunker down in shelters.

Climatic Averages for Thar

| Temperature (Spring) | 65 °F. |

| Temperature (Summer) | 75 °F. |

| Temperature (Autumn) | 50 °F. |

| Temperature (Winter) | 40 °F. |

| Low Temperature (Year) | 10 °F. |

| Low Temperature (Year) | 10 °F. |

| High Temperature (Year) | 90 °F. |

| Days with Snow | 100 days |

Wildlife

Mundane wildlife in the regions follows the predator-prey pyramid I grew so familiar with during my early adventures. Hordes of rodents infest the grasslands - mice, voles, shrews, and rabbits - and they make life miserable for the idle camper. They invade tents, devour supplies, gnaw leather, and generally make themselves a serious nuisance. The ogres of Thar, superstitious beings that they are, ascribe the damage done to the works of evil spirits and such, but the average adventurer is fully aware of the culprit's identity.

Large hoofed mammals such as deer and antelope are uncommon. Where they do exist, they run in herds of up to a dozen individuals, but pickings in the region are scarce and predators must be cunning and merciless, whether human, humanoid, or animal.

Small mammals are preyed on by larger ones like foxes, coyotes, and wolves that travel alone or in small packs. These predators have a bad reputation among the bumpkin set who regard them as vicious killers of humans, raiders of hen houses, or competitors for game. Unsurprisingly, my view of these creatures is more charitable. I have seen the valuable role they play keeping down pest populations, culling sick or dying animals, and maintaining the natural order.

Top predators include a variety of raptors. The majestic steppe eagle, a handsome beast with a lordly white-crested head, is probably the best known, although it is among the rarest. Other avian predators include kestrels, falcons, kites, and owls, as well as the shrike, a perching bird similar in appearance to a jay, whose beak and talons have been adapted to a predatory lifestyle.

These birds also feed on the rodent population of the steppes, as well as on the numerous perching birds that inhabit the region, filling the area with their songs in spring and summer, but migrating to warmer southern climes in the fall.

Humans in Thar

Although I took considerable interest in the ecology of Thar, my primary duties involved guiding caravans, accompanying adventuring parties, and assisting hunting parties. I also took part in such miscellaneous tasks as rescue expeditions, exploratory scoutings, and punitive raids against the humanoids of the region. I.ve seen the damage done to the fragile environment.

Several caravan routes crisscross the land, and are now marked by permanent wheel ruts and barren stretches where delicate grasses have been permanently destroyed. Only a few regions remain hospitable enough for encampment, and even those have been suffering under the carelessness of travelers whose idea of foraging seems to consist of killing everything that moves or grows, then sorting out the edible stuff later.

Game larger than rabbits has been nearly exterminated along caravan routes. Predators like foxes and wolves have also been systematically killed, causing massive explosions of the mouse and vole populations. Of course, the vast increase in rodent numbers has caused vast problems for caravans, with spoiled supplies and damaged equipment only the most obvious consequences. When the usual boneheaded caravan master gripes about the pests, he never realizes that his own short-sighted practices created the problem.

Several adventurers, especially the solitary guides and rangers who frequent Thar, have turned this surplus to their advantage, creating new recipes for roast rabbit, vole steak, and mouse stew, using the savory herbs that grow on the steppes. While a meal of mouse and shrew does not exactly compare to dinner at King Azoun's palace, it will keep you alive. I have resorted to such things on occasion and, although I can't recommend the experience, a starving woman can't afford to be choosy.