The Little-Lympics

Beating Gnomes at Their Own Games

by Robin D. Laws and Matthew Sernett, illustrated by Mike Vilardi Dragon #291

Sooner or later, whether she likes it or not, every adventurer is going to find herself wanting something from a gnome. That thing might be an alchemical item, a potion, the use of an exotic mechanical device, information on a ghost-haunted barrow, or even the assistance of local gnome bravos on a raid against a monster's lair. How difficult this is depends on your attitude toward the wee fellows. People who like gnomes find them fun-loving, inquisitive, and amusing. Those who don't describe them as smug, nosy, and insufferable.

Whichever camp you belong to, you should know of the existence of a shortcut to the respect and admiration of this diminutive, blue-eyed race. Gnomes love games. Games appeal to their sense of curiosity, their devotion to surprise, and their love of intricacy. Gnomes delightedly seize on any opportunity to learn or play a new game, and they've adopted many of the games played by other races. Whether it's a gambling game played with cards or a strategy game conducted on a board, chances are that many of the world's best players are gnomes. Even gnomes who don't excel at these standard games often proudly claim that their people invented them, cheerfully dismissing any and all contrary evidence.

The Spoils of Victory

Although gnomes love to win, they are generally good sports. They know full well that their games are stacked against the other races and admire outsiders for having the gumption to even try them.

DMs might give PCs that participate in gnome jumping games a +1 circumstance bonus to all Charisma-based checks when dealing with gnomes that witnessed or heard of the PC's participation. This assumes the PC lost gracefully and with good cheer. Depending on how egregiously a losing PC acted, the DM might wish to assign a circumstance penalty of up to -4.

If the PC actually manages to win a gnome jumping game, gnomes generally react with shocked admiration. Such winners often find it impossible to pay for a drink and can find themselves surrounded by admiring gnome children begging them to tell exciting stories of adventurous exploits. DMs might wish to assign a circumstance bonus of +4 to all Charisma-based skill checks to influence gnomes who saw the PC win or heard of the PC's triumph.

This is not to say that gnomes have not invented any games. Far from it: the list of gnome games would fill a small tome. They tend to be complex, their rules lengthy and fit to bursting with special cases and hidden exceptions. Gnomes love rules, feeling that simple rules are for the less sophisticated minds of taller races. Anyone who has ever puzzled over a match of Rasumian pitch-drop or frogleg's spectral hoo-hah can attest to the difficulty in outsider faces in mastering a gnome strategy game.

Unlike the more sedentary dwarves, gnomes rarely turn down a chance to get up and run around. Although they play many games requiring nothing more strenuous than the occasional stretch after too long a sit, the most distinctive gnome games are the tests of physical prowess played at festivals, weddings, markets, and holiday celebrations. Gnomes call this class of game the schelmbeng-karort-saalburort, a term that roughly translates as "the games of jumping and ducking and occasionally getting slightly injured." For reasons of space, we'll call these jumping games.

Jumping games usually pit multiple contestants, often competing separately, against an elaborate item of gnome engineering. Operated by chains, belts, and pulleys, these fast-moving machines whir, click, and groan their way through a series of rapidly executed movements, against which the competitor must demonstrate superior speed, strength, reflexes - and, occasionally, a capacity for physical punishment. Needless to say, these games are designed to favor the squat gnome physique.

It should surprise no one to learn that trophy winners at gnome carnivals are almost always gnomes. That said, a sufficiently dedicated non-gnome, even a member of the tall races, can prevail and beat the little duffers at their own games. This article is dedicated to helping you do just that.

Game Descriptions

Each game description begins with a cultural note explaining how the game fits into a gnome festival.

Contest Type: This explains who plays and when. In duels, a pair of contestants square off against one another; the winners go on to play the victors from other matches. In a race, three or more solo contestants compete to be the first to complete a task.

Equipment: This describes the machinery used and any other props or gear required to play.

Game Play: This provides a lengthier description of a typical match.

Rules: This entry tells you how to play a game-within-a-game.

Winning: This describes the game's victory conditions in simple terms.

Dizzy-Boff

This popular game tames the violence of hand-to-hand combat by arming the contestants with padded sticks instead of weapons. It adds the speed and uncertainty gnome spectators crave by placing the competitors on a fast-spinning wheel.

| Dizzy-Boff Stick | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple weapon | Size | Cost | Damage | Critical | Weight | Type |

| Dizzy-Boff Stick | Medium-size | - | 1d4/,1d4* | x2 | 3 lb. | Bludgeoning |

| *This weapon deals subdual damage rather than normal damage. | ||||||

Standard Bonuses and Penalties

Gnome jumping games are heavily skewed toward experienced contestants who happen to be shaped like gnomes.

Gnomes who grew up in gnome communities gain a +2 circumstance bonus to all Strength- and Dexterity-based skill checks listed in the game descriptions. Gnomes raised among other cultures boast the basic physique to win, but not the background, and gain only a +1 circumstance bonus.

Halflings, being creatures of a similar stature, also receive a +1 circumstance bonus, but elves, dwarves, half-elves, half-orcs, and humans all suffer a -1 circumstance penalty to all Strength- and Dexterity-based skill checks when playing gnome jumping games.

Contest Type: Duel, often played as part of an elimination tournament.

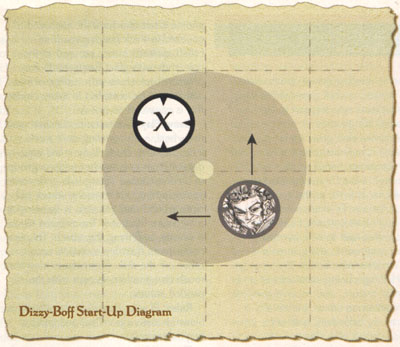

Equipment: A large circular wheel or table-top made of wood, ten feet in diameter, sits on an axis and is raised about a foot or two off the ground. During the contest, this wheel is spun by belts attached to a mill or by brawny gnomes pushing on spokes that are attached to the rim of the table.

Each contestant arms himself with a gnome-sized quarterstaff, each end covered in thick padding made of rolled, quilted cotton, secured to the pole ends with glue. Contestants may protect themselves with leather armor and leather helmets, but in many circles this is regarded as prissy.

Game Play: Contestants clamber onto the wheel, each standing on a mark indicated with chalk. They stand equidistant from one another while a group of strong-backed young lads grabs onto spokes jutting out from the wheel and runs around until the disc is spinning at a high rate of speed. The referee blows a whistle, beginning the match. The two contestants then try to knock each other off the disk. Contestants may not touch one another, except with the padded staves.

Rules: Play begins after the whistle is blown. Initiative is rolled, and combat begins normally.

The padded quarterstaves are sized for gnomes, thus characters of Medium-size or larger cannot use both ends to attack. This is considered a hazard of the game for creatures larger than gnomes, and such contestants are never armed with full-sized quarterstaves. Dizzy-boff sticks only deal subdual damage. Contestants can strike for normal damage, but suffer a -4 penalty to attacks. Striking for normal damage is considered cheating and extremely poor sportsmanship; a contestant doing so is immediately disqualified. See the Dizzy Boff Stick sidebar for more details.

Each round of combat, on his initiative, each contestant must make a Balance check (DC 12). Failure indicates that the contestant is off-balance and cannot move that round. He loses his dexterity bonus to AC, and his opponent has a +2 bonus to attack him. A failure by 5 or more indicates the contestant has fallen off the wheel. Success indicates that the contestant can move normally and attempt to strike his opponent with the dizzy-boff stick. A successful hit forces the opponent to make a Balance check (DC 12). Failure indicates that the opponent falls off the wheel. Contestants cannot take 10 on their Balance checks.

Dizzy boff contestants can also move about on the wheel. Doing so is a 5-foot adjustment and provokes no attacks of opportunity. When both contestants are on the same side of the wheel, they both receive a +2 circumstance bonus to their Balance checks. The tactic of moving on the board is often used by those who are more confident of their combat abilities than their ability to balance on the spinning wheel. Gnomes often move onto the same side of the wheel as their non-gnome opponent to "give him an even chance" and make the contest last longer.

Winning: The first contestant who knocks his opponent off the wheel three times or who knocks his opponent unconscious, wins.

Fortune's Fool

Fortune's fool is the jumping game most famous among non-gnomes. No game puts players' skill and dignity to a more exacting test than this one. It often serves as the climactic gaming event of a big festival.

The game's name refers to gnome folk wisdom, which holds that the cleverest and most agile gnome can always fall prey to the unexpected vagaries of fate. Gnomes see the game as a metaphor for life - the wise gnome remains humble, because at any moment, life can hurl a ripe, nasty tomato in his face. He also remains ever on alert, in the hopes that he can spot the worst surprises in time to duck.

Contest Type: Duel.

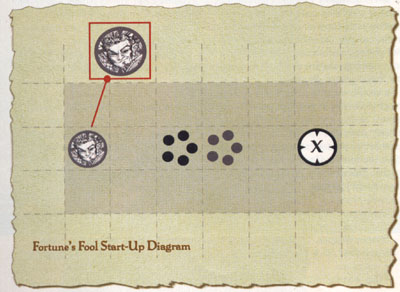

Equipment: The playing field for a game of fortune's fool consists of two main elements: a large wooden platform with a moving floor and a whole lot of tomatoes.

The wooden platform is usually 30 feet long and 15 feet wide, bordered on all sides by 3-foot-high wooden walls to prevent participants and game balls from falling out. The platform's flooring is divided into many separate pieces, each about 6 inches wide. Each piece is mounted on a fulcrum running underneath the center of the platform. Spectators operate levers allowing them to tilt a section of floor up or down like a see-saw. The levers are used to tilt a piece of flooring so that it either ramps up, down, or stays even. This makes movement difficult and scatters the game balls.

Game Play: Two contestants face off against each other, trying to pick up brightly colored balls that roll about the fortune's fool platform. All the while, they attempt to avoid tomatoes thrown by spectators.

Rules: Contestants stand in the center square of one of the short walls and face off across the length of the platform. Spectators begin moving the levers, and ten greased balls are thrown into the playing area at the center two squares. Five balls are red; five are blue. Each contestant attempts to pick up all the balls of his assigned color. Contestants are not allowed to intentionally touch an opponent's ball, but they are allowed and encouraged to lever them into other parts of the game platform (see below). Contestants aren't allowed to touch their opponent, but they can try to make their opponent fall as described below.

Play begins when all the balls have been thrown onto the two center squares of the platform. Red balls are thrown in the center square in front of the player who is trying to pick up all the blue balls. Blue balls are thrown in the center square in front of the player who needs to pick up all the red balls. Determine the initial position of each of the balls by rolling a 1d8 for each and consulting the Grenadelike Weapons diagram on page 138 of the Player's Handbook. Assume the balls only move 5 feet. Each round, at the top of the initiative, roll 1d8 for each ball to determine its new position. If a ball is against a wall, treat any result that would move the ball into the wall as though the ball stayed in its position.

The two contestants roll initiative and move to collect balls in initiative order. Moving requires a Balance check (DC 12+1 per 5 ft. moved). Failure results in the contestant being unable to move. He loses his dexterity bonus to AC and tomato throwers (described later) have a +2 bonus to attack him. A failure by 5 or more indicates the contestant has fallen prone in the square where the failure occurred, and he must spend an action standing up (picking up balls while prone is cheating). A contestant cannot move more than half-speed unless he is willing to suffer a -5 penalty to all Balance checks made during the move.

Contestants can also use the Jump skill to leap into their destination square. Thus, they need only make a DC 12 Balance check regardless of the distance moved. If a contestant leaps into a square close to one of the long walls, it causes some boards in the square across the center to abruptly rise. This causes balls in that section to move; roll for their new positions according to the rules presented above. An opponent in that square must make a Reflex saving throw (DC 12) or fall prone.

Contestants can also use the Tumble skill to move across the platform. In this case, the contestant makes a Tumble check (DC 15) instead of a Balance check. Failure of this check results in the contestant falling prone in the destination square.

If a contestant does not move, no Balance check is required. Contestants cannot take 10 on any of the skill checks required by the game because tomatoes are being hurled at them each round.

Picking up a greased ball is somewhat difficult, but it gets more difficult as contestants pick up more of their balls. The first two times a contestant picks up a greased ball, he must make a Dexterity check (DC 5) to grasp it. Picking up the third ball is a DC 8 Dexterity check. The fourth is DC 10, and picking up the fifth ball is DC 15.

Holding onto the balls isn't easy. Each time a contestant falls prone, he must make a Dexterity check (DC 15) or lose 1d6-1 balls. Dropped balls immediately scatter according to the rules presented above. In addition, each round after the first, spectators throw tomatoes at the contestants. This is a good way to involve players who are not otherwise participating in the game. Each round at the top of the initiative, four throwers are allowed to make ranged-touch attacks against the contestants. Success indicates that the contestant has been hit by a tomato. Each time a contestant is struck by a tomato, he must make a Concentration check (DC 10). Failure indicates he suffers a -1 cumulative circumstance penalty for each failed Concentration check to all Balance and Dexterity checks during that round. Spectators can throw tomatoes at whichever contestant they wish. Most of the time, the tomatoes are evenly distributed, but when someone holds five of their balls, all tomato attacks inevitably focus on him.

To make matters worse, a contestant holding no balls or a single ball can pick up a thrown tomato to throw it at his opponent. The ranged touch attack is made as normal, and the opponent suffers the usual penalties. This desperate tactic usually isn't employed unless the tomato-throwing contestant's opponent holds four or five balls.

Needless to say, this jumping game is a spectacle, and gnomes often come from miles around to watch and participate. Side bets come fast and furious during games of fortune's fool. Amateurs simply wager on a chosen player to win. Sophisticates bet on the number of tomatoes that will splatter a given competitor by the contest's end.

Winning: The contestant who has picked up all five of his balls wins if he can hold onto them for a full round.

"Ho! Well Played, Tall One!"

Winning isn't everything at a gnome carnival, especially in a game of fortune's fool.

Contestants can win the crowd's applause and admiration through panache in the face of tomato hits themselves. Contestants can throw tomatoes back at the crowd or at judges. Gnome social convention requires victims to take this in a spirit of jollity. A contestant might lose the contest but win more applause by throwing tomatoes back at the audience and by simply clowning around.

A PC wishing to do so should make a Perform (buffoonery) check or Charisma check (DC 20). Success indicates that, despite losing, the PC can reap the social benefits of winning the game of fortune's fool as described in the Benefits of Victory sidebar.

The Glittering Path

The gnome hero-god Hufurbian Mirrorbones once boasted of his privilege as a son of Garl Glittergold. It was good to be cleverer, faster, and better-looking than mere mortals, he said. Unfortunately for him, he said it within earshot of his father, who overheard him and decided to teach him a lesson. Garl Glittergold announced that Hufurbian's fabulous, jewel-encrusted hall, located in the home of the gods, would be given for a year to the winner of a special race, which he would adjudicate. Hufurbian, who perhaps was not as clever as he believed, saw this as a great gift, an opportunity to show off his superiority. He assumed the race would favor him, for he was the fastest gnome in all the land.

When the race day came, Garl arrived with a basket, from which he removed a clutch of burrowing rodents. Each of these he dipped in a pot of liquid gold. He released them, and they scampered across the gods' realm, leaving glittering dribbles wherever they went. Garl gave the contestants spoons and told them the terms of the race. The first person to gather up every last drop of spilled gold would win temporary title to Hufurbian's house.

Hufurbian's rodent was especially inquisitive, and it wriggled its way throughout the gods' realm. It ran around the forge of the dwarven god Moradin, who had sworn to beat Hufurbian when next he saw him. It wriggled through a hole down into the realm of Wee Jas, who had threatened to lock Hufurbian in a diamond coffin. It shimmied up a tree, where Obad-Hai waited for Hufurbian with scratching branches and prickling thorns.

Hufurbian returned to his manor twenty hours after the race began, to find his cousin Elbow-Wick ensconced there as winner of the race. Hufurbian won the next year, after spending a cold twelve months studying the scurrying patterns of wriggling rodents. After that, he won the contest each year, and at least on race day, he was reminded of humility's benefits.

The myth, and the game that reenacts it, recognizes the need for modesty and a sense of humor in the face of life's unpredictability.

Contest Type: Race.

Equipment: Contest organizers release from their pens a clutch of burrowing rodents. In some areas, these are sand rats; in others, gophers; and in still others, armadillos. Before release, their feet are dipped in bright paint. Organizers follow the paths the animals leave in their wake, dropping berries in the path the animals' paint-dipped feet have marked. The berries are inedible, so they're unlikely to be devoured by forest creatures before the contest begins. Their tough outer skins are painted, too, in a different hue for each contestant.

Game Play: At the banging of a gong, each contestant follows his animal's path from the animal's release point, scooping up berries. It is illegal to disturb the berries of another contestant. Judges comb the woods, following the contestants and watching out for this infraction.

Rules: Every round, each contestant must make a Search check (or a Survival for characters with the Track feat) to follow the path of the rodent. While following the path, contestants must also make a Spot check (DC 14) once each round to spy one of the berries that is near his rodent's path. The path becomes harder to find as the paint on the rodent gradually dries or is rubbed off as it runs. On the first round, the path is obvious to all contestants. On round two, a Search or Survival check (DC 2) is required to stay on track and have a chance to Spot a berry. Berries are placed approximately 20 feet from one another along the path; creatures faster than gnomes gain no advantage. The Difficulty Class for the Search or Survival check increases by +1 for every 20 ft., or round, of the race. Most glittering path races set their finishing line where the DC for the Search check reaches 11; characters without the Track feat can't follow tracks if the DC is greater than 10.

Contestants cannot take 10 on Spot or Search checks. A contestant that fails a Search check must remain behind to try again the next round. A character who fails a Spot check to find a berry can opt to remain behind and make a Spot check on the following round before making a Search check to move on, but his competitors will be making their way to the finish line.

Winning: The first contestant to follow his path correctly and cross the finish line with at least three-quarters of the berries he could have found, wins.

Jump Out

This game, a variant of fortune's fool, was invented less than a century ago by the rogue Bewilderan. It caught on quickly and is now all the rage at winter festivals. Bewilderan created it as part of an elaborate scheme to separate a half-orc baron from his ill-gotten riches, but the game went on to gain an audience in its own right.

Contest Type: Race.

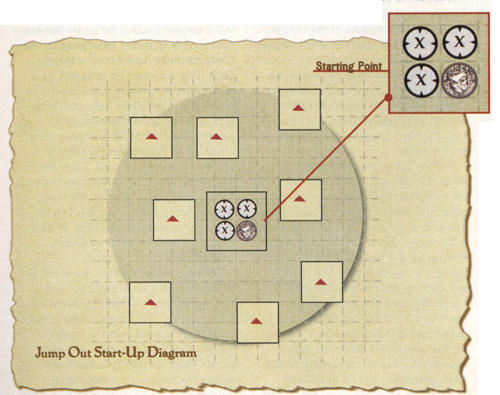

Equipment: The game requires a large patch of ice, usually a frozen pond or lake, which is then covered in snow. Hidden under the snow are a number of magic noise-making devices. These devices are often the prize possessions of a gnome community, and the loss of one is not taken lightly. After being activated, these devices make an easily distinguishable chiming noise when someone treads on the ice nearby. Traditional devices, like those invented by Bewilderan, take the shape of brass frogs.

Game Play: Before play begins, the organizers decree an ante. In poor communities, it might be as low as a few coppers, while well-heeled gnomes might play for hundreds of gold pieces.

Contestants begin in the middle of the patch of ice. Taking turns, they attempt to execute standing jumps out of the ice patch. If a contestant lands near a noisemaker, it makes a sound, which indicates he must move backward. Each time a contestant moves backward, he must add to the pot an amount at least equal to the ante.

Rules: The ice patch and noisemakers are set up before the participants arrive so that they can't figure out where the noisemakers are before the contest begins. Contestants are then lead, blindfolded and with cotton in their ears, to the center of the ice patch. They stand there while spectators throw more snow on the playing field to cover everyone's tracks. When everything is ready, spectators begin to throw snowballs at the competitors - they do this for the duration of the game. This is the contestants' signal to remove their blindfolds and earplugs and begin taking turns jumping.

The DM should decide how many noisemakers there are and place them in a fair distribution pattern. Their placement should be kept secret from the players. Usually, there are enough noisemakers to make it challenging, but not so many that the contestants become frustrated or lose their shirts to the winner. Typical jump out games include up to eight participants on a 30-foot diameter patch of ice with six to eight noisemakers hidden under the snow. Noisemakers detect the presence of living creatures of at least Tiny size within 5 feet and chime so long as such a creature remains nearby. See the Jump-Out Noisemakers sidebar for a full description of these magic items. The diagram shows an example of a typical jump out set up.

On his turn, each contestant makes a Concentration check (DC 10) to keep his mind on the game under the onslaught of snowballs from the spectators. Failure indicates that the contestant suffers a -2 circumstance penalty to his Jump and Balance checks during his turn. He must then make a Balance check (DC 11), failure indicates he is unable to move and it the next contestant's turn. If he succeeds, he can then make a Jump check to move into another square. All jumps are standing jumps. If the square is one of the 5-foot squares adjacent to the noisemaker, it chimes, and the contestant must step back 5 feet. All contestants can then make a Listen check (DC 15) to figure out where the noisemaker is located. This continues until someone escapes the ice patch.

Winning: As soon as a contestant exits the ice patch, he is declared the winner and the game ends. The winner gets the contents of the pot.

Using Gnome Games

Your players might well enjoy running their PCs through these games-within-the-game as is. The glittering path creates a sort of adventure, in its own abstract way. The gambling element of jump out might appeal without any extra effort on your part. For the other games, you'll find you can pique plenty of interest by making an attractive and valuable item the prize. That said, these games can also serve as springboards for other story ideas. A game of dizzy-boff can provide a non-lethal forum for a PC to meet a future enemy, finding out just how tough he is. A fortune's fool match could get out of hand and turn into a full-contact sport. You could designate a particular place on the glittering path to trigger an encounter with a monster, wild animal, or to offer a clue to a new or ongoing mystery. A sinister NPC might rig the magical devices used in jump out to deal damage when characters land near them. Or the noisemakers might get stolen right under the PCs' noses, causing the gnomes to suspect the PCs of wrongdoing.

However you decide to introduce gnome jumping games into your campaign, remember that they offer more than fun minigames to play out during your D&D session. They also offer unique and exciting opportunities for roleplaying interaction with gnomes and are a great way to introduce your players to gnome culture.

Jump-Out Noisemakers

Originally invented for the jump-out game, jump-out noisemakers often to find use in the very serious business of adventuring.

As a standard action, a noisemaker can be activated. An activated noisemaker chimes at a volume slightly louder than normal speech so long as a living, corporeal creature of Tiny size or larger remains within 5 feet. Adventurers find it useful to set these innocuous looking devices near their resting places as alarms. Jump-out noisemakers have also been found to be useful when fighting creatures that can render themselves invisible. Noisemakers can be deactivated as a standard action by holding it and speaking the command word.

Caster Level: 3rd; Prerequisites: Craft Wondrous Item, alarm; Market Price: 2,700 gp; Cost to Create: 1,300 gp + 108 XP.